1) Nothing changes. This is a commonly held truth. Sometimes this is cause for complacency, sometimes cause for hopelessness.

2) Everything changes. This is also a commonly held truth. Sometimes this is cause for fear, sometimes cause for hope.

Are these both true? Absolutely. But in which cases should we learn to accept stasis and in which cases should we expect change?

Today, I want to explore the fact that nothing ever changes.

In Part 2, we’ll tackle the fact that everything changes.

In Part 3, we’ll conclude by parsing out what change means for American democracy’s stability.

Geography is destiny; this is a frequent assertion of historians and geographers. For good reason, since examples abound of certain places seemingly trapped by a repetitive fate.

Today, Ukrainian special forces, missiles, and naval drones try to reconquer the Crimean peninsula and the Kerch strait from Russian invaders. In 2014, Russian subversion seized the territory from Ukraine. In the Russian Civil War, the White Russians made their final stand in the Crimea. From 1854-1856, English, French, Turkish, Sardinian, and Russian forces battled over the Crimean peninsula. Hundreds of thousands died. In the eighteenth century, the Russians seized it from the Turks. In the fifteenth century, the Turks seized it from the Mongols. The earth itself, if it could feel, would be unsurprised by this violence. The Crimean promontory into the Black Sea makes the territory strategically valuable. Therefore, people fight over it constantly. Even two thousand years ago, Strabo, a Greek historian reported that the 1st century BCE, the Romans granted Mithridates of Pontus the Cimmerian Bosporus, the modern area of Crimea and the strait of Kerch. Then, Asander defeated him, took over the kingdom, and built a 35-mile wall with 36,000 towers to secure Crimea. Eventually the Romans accepted this outcome. Fighting. Fortifications. Thousands of dead. Thousands of years. Nothing changes.

Image: The Crimean War in 1854

Geography is destiny in Israel and the ancient western Levant. Today, Israel fights against a Sunni theocracy in Gaza, a Shia theocracy in Lebanon, and a Persian theocracy in Iran. Fighting for control of this narrow strip of land is old, old, old. In 1917, the British fought the Germans and the Ottomans in First and Second Battles of Gaza; though the British lost, they eventually ruled. Before them, the Ottomans invaded Jerusalem in the sixteenth century. Before them the Crusaders conquered the land. Before them, Caliph Omar led in Arab invaders. Before them, the Byzantines ruled. Before them, the Romans under Pompey in 63 BCE marched in. Before them Jews ruled themselves. Before them, the Greeks invaded. Before them, the Jews again. Before them, the Persians. The Babylonians. The Assyrians. The ancient Israelites. The tribes of ancient Canaan. And who knows who came before them, before recorded history. The endless conflict is not surprising to a geographer. The region sits at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe. It depends upon rainfall for food and so exists far more precariously than the nations that flank it: on one side, the fertile Nile River delta and on the other the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that cradled Mesopotamian civilization. Those two fertile regions provided agricultural abundance and thus powerful kingdoms, leaving the Levant surrounded by powerful empires. As a result of geography: violence and conquest have long been its fate.

Image: Eight century BCE, Assyrian conqueror escorting captured Israelites

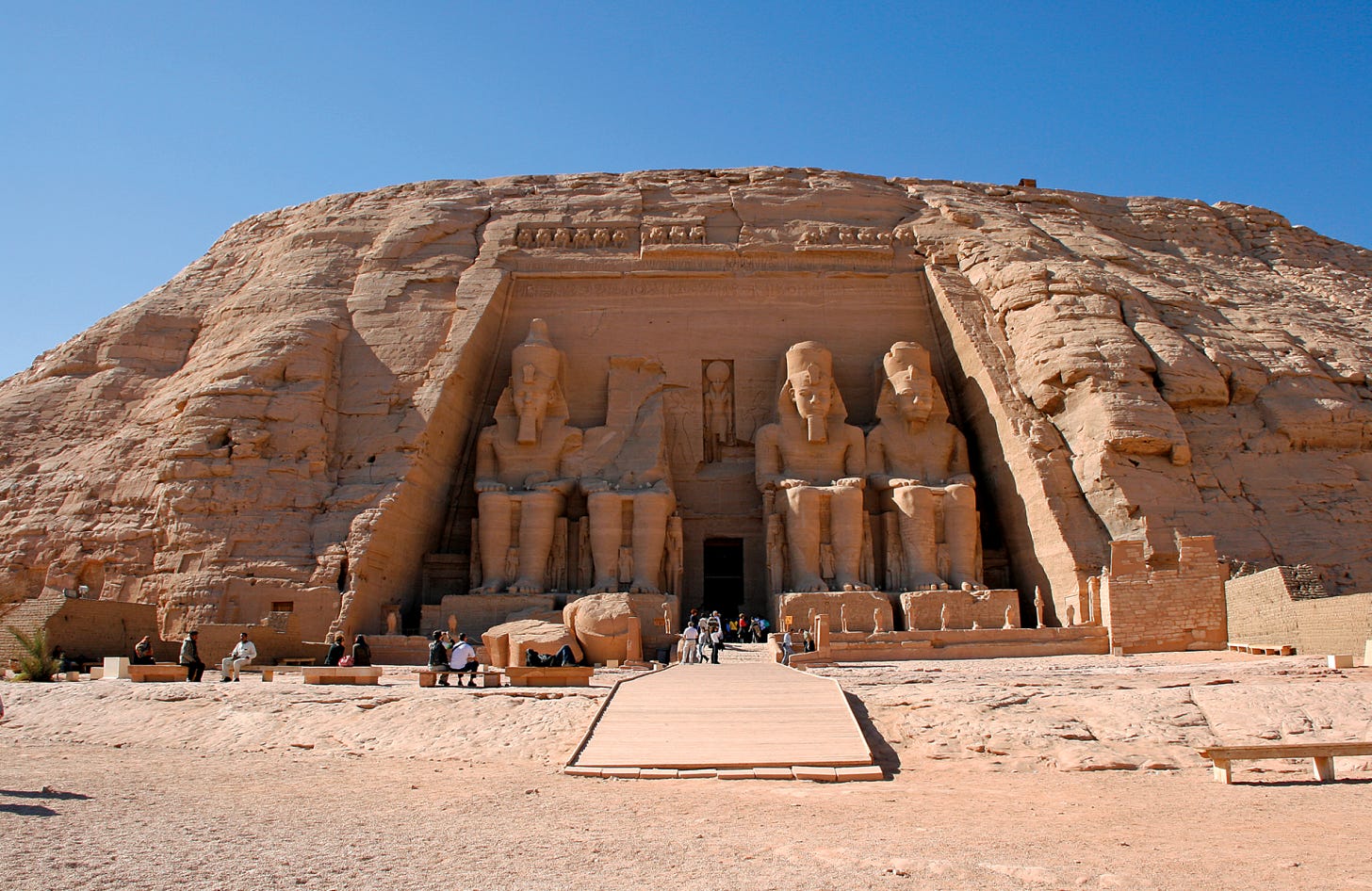

Continuing south, the Nile River can explain why for millennia Egypt stayed powerful, and little changed except which Egyptian dynasty ruled. The Egyptian empire lasted so long that according to Plato their priests said to Solon, the architect of Athens’ democratic constitution, “O Athenians, you are mere children!” The Nile river furnished Egypt with vast stores of food easily. Large deserts protected it from foreign conquest. As a result of geography, Egypt enjoyed centuries of security and easy prosperity. This shaped its culture: Egypt’s abundant prosperity and security led to a strong monarchy and to believe they could do anything. The Egyptian worldview became more optimistic than that of other ancient civilizations. [i]

Image: Thirteenth Century BCE testaments to Egyptian power and abundance still stand today

Similarly, America, arguably owes much of its cultural optimism to its geography. The last foreign occupation of the American mainland occurred more than two centuries ago during the War of 1812. Since then, American soil has suffered air attacks by the Empire of Japan and by Al Qaeda each of which killed thousands, and as a raid by Pancho Villa. All of these attacks, however, lasted a single day. America’s two vast oceans make foreign invasion a logistical undertaking of immense proportions. Facing just two land neighbors, both of whom are less populous and far less powerful and on friendly terms, American enjoys a level of peace few nations on earth have. Since 1865, America’s security from foreign threats has radically differed from most other countries on earth, who have been occupied or faced the threat of occupation for much of their history. Nations with enemies at their gates must think with a realpolitik that America is fortunate to be able to ignore.[ii]

Similarly, democratic norms and values, the core of this blog and my book can be explained by geography, too. Many scholars have done exactly that.

Aristotle held that geography shapes society. That in colder regions people have to have more spirit and are tougher, have a view of being indomitable because of the harsh climate. As a result, they enjoy more freedom.[iii]

French Enlightenment philosopher Charles de Montesquieu wrote similarly that “the barrenness of the earth renders men industrious, sober, inured to hardship, courageous, and fit for war; they are obliged to procure by labor what the earth refuses to bestow spontaneously.” When individuals must toil for their own food, self-reliance becomes part of their character, they treasure liberty, and democracies are born. By contrast, when the land is fertile, luxury leads to indolence and monarchies emerge. “The barrenness of the Attic soil,” near Athens, “established there a democracy; and the fertility of” Spartan territory, led to “an aristocratic constitution” there.[iv]

Eighteenth Scottish Philosopher Adam Smith similarly noted that people in trading and manufacturing towns “are in general industrious, sober, and thriving; as in many English, and in most Dutch towns.” By contrast, in those towns “principally supported by” a monarch, most people are “idle, dissolute, and poor; as at Rome, Versailles, Compiegne, and Fontainbleau.”[v] Because entrepreneurial societies create a culture of hard work – “frugality, economy, moderation” – they develop the self-discipline which creates robust democracies.

In other words, once the die was cast in the shape of the Earth, things pretty much were set. Nothing would change.

In military terms, a valuable hill, port, strait, or river, will always be a valuable asset and armies will fight for it.

In cultural terms, the difficulty of agricultural cultivation will make people harder-working and more independent than those who live in abundant circumstances.

Nothing changes.

If nothing changes, then there is nothing to worry about in a country like America where it enjoys military security. Everything that works now will continue to work.

There is one minor problem in arguing that nothing ever changes, which is the fact that nearly everything changes.

Which is the subject we’ll pick up next week.

*Terms & Conditions: Provide proof of purchase of Pedestal, your subscriber info, and we will send you a prepaid package label for you to return the book for a full refund.

[i] Kagan, Donald, Steven Ozment, and Frank M. Turner. The Western Heritage. Second edition, brief edition, combined volume. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1999. p.8.

[ii] On America’s being free from the fear of foreign invasion see for example: 1) “American Isolationism in the 1930s” US Department of State, Office of the Historian, available online: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/american-isolationism. 2) Stilwell, Blake, “5 Reasons Why Geography Is America's Greatest Weapon Against an Invasion” Military.com. March 11, 2022. Available online: https://www.military.com/history/5-reasons-why-geography-americas-greatest-weapon-against-invasion.html and 3) Wertheim, Stephen. “Why America Can’t Have It All” Foreign Affairs, February 14, 2024. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-america-cant-have-it-all?check_logged_in=1&utm_medium=promo_email&utm_source=lo_flows&utm_campaign=registered_user_welcome&utm_term=email_1&utm_content=20240516Wertheim notes: “More than any major power, the United States, endlessly innovative, militarily peerless, shielded by two oceans and nuclear deterrents, should be master of its fate. It should look out at the world and see opportunities to seize and choices to make.”

[iii] Aristotle, Politics, VII 7 1327b: 20-37

[iv] Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws, XVIII: 1-4.

[v] Smith, Adam, Wealth of Nations, 232.