The Madness of Crowds (Part 1 of Infinite)

The Human Instinct to Thoughtlessly Mimic Others Accelerates Democratic Peril

Call it the Chicken Tender madness. A story reported that New York City had cut $60m from school lunches. This was incorrect. The story did not understand the city’s (admittedly complex) budget. The city actually replaced $60m of city funds for school meals with $60m of federal funding (see the budget, page 93).

But for many, the temptation to believe that budget cuts had deprived students of prized foods like chicken tenders, dumplings, bean and cheese burritos, and cookies was too good to be false.

So the stories piled on, parroting the news without actually understanding the budget (ex: the Guardian) These writers and their followers could not help harmonizing with a chorus of beliefs they felt had to be true, even when false.

This small instance is one of countless examples demonstrating how terrible we human beings are at thinking for ourselves. We repeat back what we hear around us without thinking. The human phenomenon of “groupthink” was coined in 1952 by William H. Whyte Jr. to capture that “instinctive conformity” that “is a perennial failing of mankind.” Our hardwired instincts cause us follow the beliefs of those around us even to the detriment of society.

This human instinct for mimicry is particularly malicious in America today because the mindset that divides Americans into rival camps and stokes distrust of each another is the only actual peril facing the United States. So the blind willingness to believe what other people say acts as powerful fuel for fraternal hatred.

The best book on the subject I have read is Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, published in 1841. The dangers posed by popular human impulses — with regards to money, diseases, social norms, superstitions, etc. — were obvious 200 years ago.

In fact, long before that. We see it in the 1st Century CE, where Roman historian Tacitus teaches us when a few citizens began spying on each other, everyone followed. “This was the most dreadful feature of the age, that leading members of the Senate, some openly, some secretly, employed themselves in the very lowest work of the informer.” Everyone was “infected with the contagion of the malady.” The “innate tendency of men [made] them quick to follow where they are slow to lead.”[i] Once some people started informing against fellow citizens, everyone became an informant.

In 1144, the madness of crowds appeared in Norwich, England, when a boy was found dead in the woods. Over the years, a fabricated tale emerged, charging that the Jews of Norwich had murdered him, intending to drink his blood as a remedy for hemorrhoids. Over the next twenty years, this invention won widespread acceptance and copycat fabrications followed: in Gloucester in 1168, Busy St. Edmunds in 1181, and Bristol in 1183. During the Third Crusade, in 1189-90, English mobs massacred the Jews in York, Norwich, and elsewhere over this blood libel. Similar patterns of lies winning quick mob followings leading to massacres fill the tomes of Jewish history. As historian Paul Johnson notes, “as with all conspiracy theories, once the first imaginative jump is made, the rest follows with intoxicating logic.”[ii]

In Milan, in 1630, when a plague struck, Milanese citizens came to believe that emissaries of the devil or foreign powers were responsible for: poisoning the well water, the corn in the field, the fruit of the trees, the walls of houses, the street pavement, and door handles. People were alert for the devil’s emissaries. As a result, like in the madness of ancient Rome when all citizens turned informants, anyone who wished to get rid of an enemy simply had to say they saw them smearing ointment on a door and the mob would come and kill them. Innocent people were put on the rack until they confessed. Crowds came to witness the execution—which, of course, spread the disease faster.[iii]

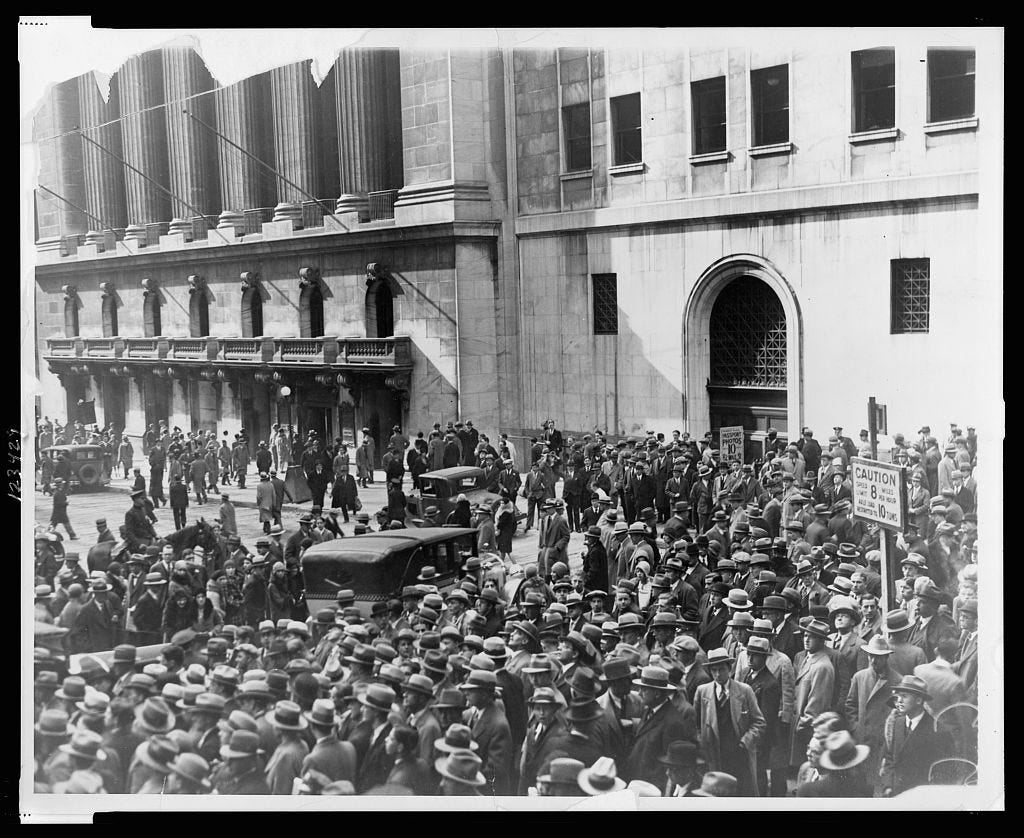

During the South Sea Bubble investor frenzy of the 1710s, as in many economic manias, investors threw their money at any opportunity, hoping for quick riches. Among these ventures was “A Wheel of Perpetual Motion.” Another was “an undertaking which shall in due time be revealed.”[iv] By the stock market crash of 1929, human nature had not changed. Speculators so blindly trusted investment trusts that theirs were “undertakings the nature of which was never to be revealed, and their stock also sold exceedingly well.” For a short time after each crash, humans resist the disease of following their peers, avoid the “contagion of… unfounded fears,” because a “speculative outbreak has a greater or less immunizing effect;” eventually, however, “with time and the dimming of memory, the immunity wears off” and the madness of crowds, returns.[v]

I cannot catalog humanity’s crowd following forever, not because of my eventual mortality but because the examples will, sadly, never cease. The human propensity to conform to the behavior of those around us is sempiternal.

It therefore should be respected and feared.

Especially in a democracy.

For ideas are, arguably, the single most powerful force in human history, almost certainly so since the French Revolution. And in political discourse in a democracy, citizens constantly engage with ideas, both overtly and in ways we don’t even see. The madness of crowds causes these ideas to spread like wildfire, like a contagion. As the 20th century philosopher Isaiah Berlin noted “our philosophers seem oddly unaware of these devastating effects of their activities,” for ideas “sometimes acquire an unchecked momentum and an irresistible power over multitudes of men.”[vi]

When we hear myopic or demeaning ideas – as many ideas espoused by illiberal leftists and rightists are – our human penchant for mimicry becomes an accelerant of destruction, the gasoline of internecine conflict. In America, we have been fortunate to dodge the awful destruction of each other for almost all of our history. There’s no reason we can’t keep it that way. There’s also no reason it must remain that way.

In our own times, just as in ancient times, humans do and think like others around them. As social creatures, we will follow the behaviors of those around us even when it condemns us and others to death.

The chicken tender madness is a jocular example. But the principle is not. We should aim never repeat a statement without understanding it ourselves. It’s a high bar. Which is a good place to start.

[i] Tacitus, Histories, 1.55 and Annals, VI.7

[ii] Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, 1987. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 209-211.

[iii] MacKay, Charles. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, 1841. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1980. 271.

[iv] Bagehot, Walter, Lombard Street, 130-131.

[v] Galbraith, John Kenneth. The Great Crash, 1929. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1955 (1961) , 54, and 174-176. David Ricardo uses the pithy phrase: the “contagion of the unfounded fears” to describe the 1797 British financial crisis. See: Ricardo, David. The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1818 (2004), 243 (chapter XXVII)

[vi] Berlin, Isaiah. “Two Concepts of Liberty,” Four Essays On Liberty. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1969, p. 118-172.